Coral is a deposit of lime or calcium carbonate formed by coelenterates. The coral colonies grow continuously in size by budding of the polyps and often form extensive masses known as coral reefs. According to T. Wayland Vaughan (1917), “A coral reef is a ridge or mound of limestone the upper surface of which is near the surface of the sea and which is formed of calcium carbonate by the action of organisms chiefly corals.” The coral reefs are –banks of coral rock built upon the sea bottom about the shores of tropical islands.

Coral

Corals are marine colonial, polypoid coelenterates, looking like sea anemones and living in a secreted skeleton of their own. Their calcareous and horny skeleton is also known as coral.

Coral Reef

When corals gather in a place and build an ample space or reef. Then it is called a coral reef. Cora reef is one kind of algae. It is a massive structure of CaCO3. It is called Cnidarians. e.g., Sea anemones.

- Calcareous and horny skeletons are known as coral.

- Usually, coral is two types such as corallites and corallum

- Each coral is small in size.

- Coral is the component of the coral reef.

- Coral is found in many places of the water body.

- When corals gather in a place and build a large space or reef. Then it is called a coral reef.

- It is usually three types: fringing, barrier, and atoll.

- Coral reefs are larger than coral.

- A coral reef is the sum of coral (solitary and colonial coral reefs).

- A coral reef is found in shallow and warm seawater.

- Polyp is the life stage of coral. It is a sac-like stage. Polyp is the functional stage of coral.

- A coral polyp is a colony of polyps. It is the jointed thin tissue.

- Zooxanthellae is one kind of algae that helps the formation of coral reefs. In the coral reef, photosynthesis occurs in zooxanthellae. e.g., Dinoflagellates.

Process of Coral Reef Formation

There are many processes of reef formation. A necessary process is given below:

- Reef coral: The massive reef is built of the calcium carbonate skeletons of billion polyps. Polyps are the sac-like stage, with the mouth and tentacles on top. Reef-building corals are the primary architects of coral.

- Coral polyps: The little polyps build coral reefs. Coral polyps are not only small but deceptively simple in appearance. Most corals are colonies of many identical/ polyps. All reef-building coral contain symbiotic zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae enable the coral to deposit calcium carbonate faster.

- Coral nutrition: Coral nourishes itself in a remarkable number of ways. Zooxanthellae provide the most essential source of nutrition. Coral can also capture zooplankton with tentacles or mucus nets, digest organic materials outside the body with mesenterial filaments or absorb dissolved organic matter from the water and they make it to the coral.

- Other reef builders: Encrusting coralline algae help build the reef by depositing calcium carbonate resisting wave erosion, and cementing sediments. The accumulation of calcium carbonate sediments plays an important role in reef growth. Coralline green algae and coral rubble account for most sediments, but many other organisms also contribute.

Factors Affecting Coral Reef Formation

Factors affecting coral reef formation are given below.

Light:

Light is one of the most important limiting factors for coral reef formation. Sufficient light must allow photosynthesis by the symbiotic zooxanthellae in the coral tissue. Without enough light, the photosynthetic rate is reduced, and with it, corals’ ability to secrete calcium carbonate and produce reefs.

Temperature:

No reefs develop where the annual mean minimum temperature is below 18°C. Optimum reef development occurs in water where the mean annual temperatures are about 23-25°C. Some coral reefs can tolerate temperatures up to about 36-40°C.

Depth:

Coral reefs are also limited by depth. Coral reefs do not develop in water deeper than 50-70m. Most reefs grow in depths of 25m or less.

Salinity:

Sea water of average oceanic salinity (between 30-40 ppt) to which corals are restricted is usually saturated in calcium carbonate. So that adequate Ca” is available in the skeleton-forming process. Floods of fresh water may destroy life on inshore fringing reefs. Salinity is the most important factor that acts to resistant coral reef development.

Sediment:

Sediment also affects the formation of coral reefs. It set out on the coral reefs harms coral reefs. Sediment in the water or turbidity has an additional adverse effect: it reduces the light necessary for photosynthesis by the zooxanthellae in the coral tissue. As a result, coral reef development is reduced in areas of high turbidity.

Wave action:

Coral reef development is more significant in areas subject to strong wave action. Coral colonies, with their dense, massive skeleton of CaCO3, are very resistant to damage by wave action. Wave action provides a constant source of fresh, oxygenated seawater and prevents sediment from setting on the colony.

Pollution:

Pollution is another important factor that acts to restrict coral reef development. High concentrations of nutrients pollute the water, and coral reefs reduce in the polluted area. Coral reef formation occurs with low nutrients.

Types of Coral Reefs

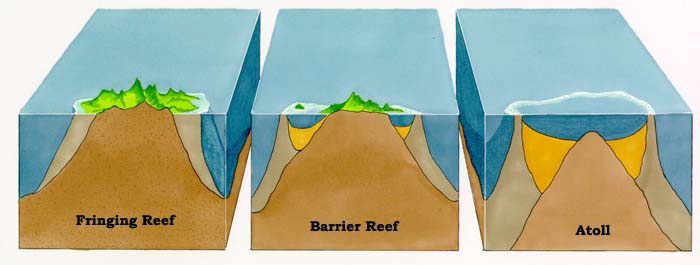

Scientists have identified three major types of coral reefs; fringing, barrier, and atolls.

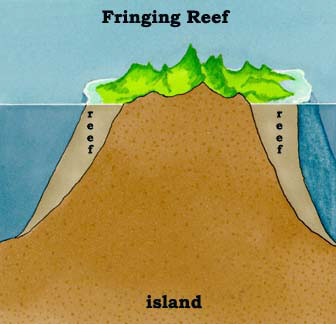

Fringing reefs

The coral reefs growing in shallow waters, closely bordering the shores of some volcanic island or part of some continent, are termed the fringing reefs or shore reefs. They represent the youngest and the simplest reef type. As their name expresses, they lie close to the shores and are comparatively small in breadth. They extend from the coast a few meters to 0.5 kilometers out as a bench or platform with its surface more or less level.

The most active coral growth occurs at the outer or seaward edge of the reef platform, called the reef edge or reef front. It is covered by firmly fixed animals and plants. Between the reef edge and the shore is a slightly lower and more or less flat surface, called the reef flat or seaward flat, mainly composed of coral sand and mud, dead and living coral colonies, other animals, and other debris. The flat is ordinarily submerged at high tide, but at low tide, the water seems to run rapidly, exposing the whole surface of the flat almost simultaneously.

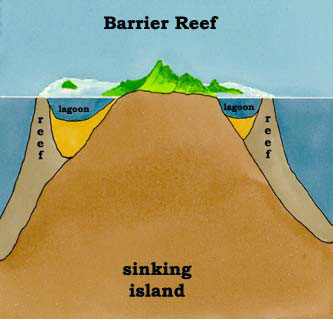

Barrier reefs

Barrier or encircling reefs also parallel coasts, like the fringing reefs, but they are located farther from shore. The stretch of water separating the barrier reef from land may be one to seven kilometers wide, known as the lagoon. It is 20 to 100 meters deep and suitable for navigating the largest ships.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the world’s largest and most noted. It is an enormous coral structure extending along the northeastern coast of Australia for over 2,000 kilometers. Over 200 species are contributing to its formation. Hundreds of patches of oval or elongated coral islands are built up to the surface, all with their fringing reefs.

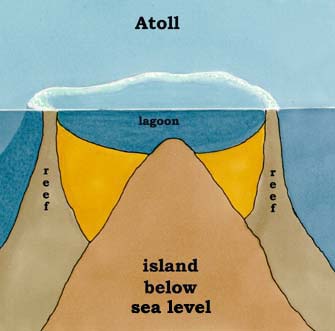

Atoll

An atoll, a coral or lagoon island, is a ring-like, circular, or horse-shoe-shaped reef partly or wholly enclosing a central lagoon instead of an island. The lagoon varies from a few hundred meters to 70 or 90 kilometers in diameter and 20 to 90 meters in depth. Thousands of atolls dot the Indo-Pacific region forming nearly 90% of all coral formations.

Fauna of Coral Reefs:

A tropical coral reef is a shelter or substratum for several thousand different kinds of animals occupying various ecological niches. Thus, a coral reef represents a living geographical phenomenon with the most fascinating and complex marine communities and is attractive from ecological and biological standpoints. The principal builders of coral reefs are the stony corals (Madreporaria), but other essential contributors are the coralline algae or branching algae impregnated with lime, Foraminifera (Protozoa), hydro corallines (Millepora), and various calcified alcyonarians (Tubipora and Heliopora),

Besides, the coral clumps attract a host of other animals. The cracks, crevices, and chasms between masses of corals furnish shelter to innumerable brightly-hued fish and representatives of practically every phylum in the animal kingdom, such as crabs, shrimps, barnacles, worms, starfishes, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, octopuses, snails, clams, cowries, sponges, hydroids, bryozoans, sea-anemones, and coral polyps. Some of them, such as boring sponges, mollusks, worms, barnacles, etc., break down the coral skeletons.

In contrast, others, such as algae, sponges, hydroids, tunicates, etc., cement the debris together, forming a foundation for further coral growth. The coral bed, with its multitude of organisms of varied shapes and colors, viewed through the deep-blue water, presents one of the most beautiful sights in the world, rivaling the most gorgeous flower gardens.

Major Threats to Coral Reefs

There are many reasons why coral reefs are threatened throughout the world.

Natural damage

Because reefs thrive only under particular conditions, they are frequently disturbed by natural events such as storms, temperature fluctuations, predator outbreaks, terrestrial run-off, and climatic disruptions. Disturbance can cause corals to lose their zooxanthellae, grow more slowly, and produce fewer larvae.

Unfavorable environmental conditions

Corals flourish at temperatures of 26-27c; below 18°C growth is much reduced, and at higher temperatures, bleaching occurs. Most coral needs clear water because turbid, silty water inhibits light penetration and thus impedes the symbiotic zooxanthellae from photosynthesizing sediment settling on coral polyps also causes direct stress, smothering the polyps and inhibiting feeding and respiration. Salinity should ideally be in the 30-36ppt which means that corals do not thrive in areas of heavy freshwater run-off. They also need regular clean, well-oxygenated water; coral growth will be hampered.

Hurricanes

Tropical storms (the most dramatic of which are known as hurricanes, cyclones, or typhoons in different parts of the world) can devastate reefs. The heavy rain and silt load often accompany tropical storms and may also damage reef organisms. Storm damage is also a regular event on reefs in northern latitudes, such as those around the Hawaiian archipelago. This partly explains why these northern reefs need to be more well-developed. For example, reefs outside the hurricane belt in the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf do not suffer from such an impact.

Diseases

The diseases of marine species are still poorly understood and documented. Two coral diseases, white and black bands, occur throughout the Caribbean and have recently been reported in the Red Sea (Peters, 1988). These have contributed to much of the coral mortality observed in Florida and the US Virgin Islands. As reef habitats become more “stressed” through siltation, pollution, and other impacts, their communities may become more susceptible to disease. There is some evidence that coral disease in the Red Sea was triggered by pollution.

Sea temperature fluctuations

Pacific coral often bleaches during an El Nino- a periodic disruption of the weather pattern that causes a warm current to sweep into the usually comparatively cold water of the eastern Pacific. The El Nino of 1982-83 caused widespread coral death in the east of the Pacific and may even have resulted in the extinction of a coral species (Glynn et al., 1988)

Human activities affecting reefs

Natural impacts on reefs are generally localized, short-duration, and do not affect all species. Human activities, however, frequently lead to more widespread and long-lasting disturbances. Reefs can often withstand a certain stress level, such as low-level tourism, for a long time. However, introducing a second impact (increased pollution, a predator outbreak, hurricane, etc.) may tip die balance and result in significant damage. The following is a brief review of all the leading causes of reef damage that result from human activities:

Siltation

High silt levels affect reefs by lowering the light intensity, thereby hindering photosynthesis in the zooxanthellae and settling on the reef, smothering the coral and preventing the larvae from settling. Siltation also occurs due to many human activities, and these may be among the most significant threats facing reefs today.

Pollutions

Pollution is one of the greatest threats to all marine environments and significantly impacts reefs.

Nutrient pollution: High levels of nutrients in seawater encourage the growth of seaweeds and phytoplankton, which deplete oxygen, reduce light, and may entirely smother the corals. Nutrient enrichment, principally created by sewage and fertilizer run-off, is cited as a significant cause of the decline of reefs in Florida and other parts of the world.

Oil pollution: More recent studies over longer periods suggest that oil has a serious long-term impact under certain conditions. It isn’t easy to generalize as the effects depend on many factors, such as the type of oil. The quantity, the weather conditions, other pollutants in the spill, and remedial action are taken.

Other pollution: There is some evidence that corals take up a variety of substances, such as heavy metals, from water and that these may have a detrimental effect on their growth.

Damage caused by recreation and tourism

In the late 1980s, nearly 60 countries cited tourism as a reef threat (UNEP/ IUCN, 1989). Tourism affects reefs in several ways poorly planned hotel development, increased sewage pollution, and greater exploitation of reef resources to satisfy the demand for food and curio. Tourism affects reefs directly through damage inflicted on roots by anchors, boat groundings, and tourists trampling on the corals.

Overexploitation

Overfishing can have serious ecological implications. Many fish caught for food (e.g., snapper, grouper, hogfish, triggerfish, etc.) are predators that feed on herbivorous fish and invertebrates, such as sea urchins, which play essential roles on the reef. Many other commercially important reef invertebrates such as spiny lobster, queen conch, sea cucumber, mother-of-pearl bearing mollusks, and other ornamental shells and corals are also being overexploited (Wood and Wells, 1988).

Damaging fishing methods

Many fishing methods, particularly the more modern ones, damage reefs. Dynamite fishing is one of the most destructive and, although illegal in most countries, is still widespread. Sodium cyanide which poisons and kills other reef life, is still commonly used to collect aquarium fish.

Ciguatera

Ciguatera, or fish poisoning, is a significant problem in some reef fisheries, and there is growing evidence to suggest that it is caused by reef damage (Anderson and Lobel, 1987)

Destruction of habitats

Coastal engineering and development projects often radically alter reef habitats. When these involve processes like dredging and infilling, they can destroy reefs. The destruction of mangroves and sea grass beds may significantly impact neighboring reefs, increasing siltation and disrupting nutrient recycling and other essential processes.

Global warming

Global warming could affect reefs in two principal ways sea level rise and higher seawater temperatures.

- Sea-level rise: the impact of this on reefs will depend on whether or not the rate of sea-level rise is faster than average reef growth rates. There are likely to be regional differences, as both sea-level rise and reef growth rates vary from location to location. The Great Barrier Reef could initially benefit from a rising sea level, but reefs in the Caribbean will likely struggle to keep up with even slower rates of sea-level rise.

- Increased sea temperatures: Many recent outbreaks of coral bleaching have been found to coincide with high seawater temperatures. Temperature rise is sometimes connected with El Nino, whose impacts extend well into the Indian Ocean. Higher sea temperatures will have a greater impact on reefs than sea level rise, as wide-scale coral bleaching could seriously affect reef health.

Approaches to reef conservation and Management

Successful reef management will typically require a combination of different approaches, depending on the sea area’s characteristics (biological, socio-economic, etc.). Several aspects of reef management are described below-

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

The success of this approach will depend on how much the people involved in these activities understand their impacts on the environment and the extent to which these people are engaged in management plans to regulate them. Effective enforcement mechanisms are also essential. The intention is to manage all activities in the coastal zone unified, considering different users’ interests and ensuring that vulnerable ecosystems such as reefs are protected.

Community Involvement and Management

It is essential to recognize that local people play an integral part in reef conservation since they, rather than government agencies or outside, are responsible for managing their natural resources. Local community management of small coral reef areas is proving highly successful in the Philippines, where local villages have set up and managed some seven or eight marine conservation areas.

Prevention of sewage pollution

Local, regional, and national authorities must ensure appropriate control of sewage discharge in all coastal areas. The most straightforward measure is to divert the outfall away from the reef, into deep water, or onto an open, well-flushed coast. Meanwhile, sewage from boats, especially when they moor in popular anchorages, also contributes to reef degradation. This should be prevented through the use of an onboard holding tank. Ports in areas with a heavy volume of shipping and tourism require better regulations and disposal facilities.

Prevention of oil pollution

Many countries are taking action to prevent marine pollution from oil spills and have introduced appropriate legislation. Efforts are needed to motivate and help the relevant authorities to reduce pollution and wasteful operations. The risk of pollution can be minimized if the consequences are understood if there are adequate facilities for dealing with the problem, and if people have been trained to use them; nevertheless, the accident can occur.

Prevention of siltation during dredging

Silt curtains, berms, and other mechanical aids are now available and can isolate work sites and prevent sediment from escaping onto adjacent reefs. Such devices should be more widely promoted, and people should be taught how to use them correctly. Guidelines and manuals, training courses, and workshops could help ensure this.

Prevention of siltation from soil run-off

Much soil erosion and subsequent run-off can be prevented by adopting good forestry practices and less intensive agricultural techniques, such as leaving natural vegetation along streams and contour plowing and planting.

Reef restoration

Management activities that attempt to maintain the quality of coral reefs may be supplemented by programs to restore or speed up the recovery of heavily degraded reef areas. Such programs involve:

- Transplanting coral.

- Cementing fractured and dislodged corals.

- Creating new artificial hard substrata upon which corals can settle, and reefs eventually develop.

Sustainable Management of reef fisheries

Closed areas or reserves could play an important role in reef fishery management, and there is increasing enthusiasm for using such areas for this purpose. Community fishery management can help reduce overfishing in coral reef areas. Sustainable fishery management can only succeed if alternative occupations and new sources of income are provided for fishermen and others whose earning capacity may be affected by regulations that reduce their catches. Establishing mariculture (farming marine plants and animals) and artificial reef programs is possible.

Sustainable Management of tourism

Mass tourism generally threatens reefs much more than small-scale tourist efforts. Any new large-scale development should therefore be discouraged in sensitive reef areas. Measures can be taken to reduce the impact where many developments already exist and new ones cannot be prevented. Careful planning for tourism within a coastal zone management plan can substantially reduce damage.

Information gathering and monitoring

Although information exists on the general status and conservation requirements of the world’s coral reefs, it is not available in a form that permits comparison and assessment of priorities. This information needs to be centralized and coordinated in databases at the regional, national, and global levels; if the data were organized in this way, they could help conservation agencies at all levels to develop programs and assist Governments in setting priorities.

Monitoring coral reefs in the field over a long period is extremely important. Monitoring provides a record of changes in reef health, improves our understanding of natural fluctuations in reef health, provides early warning of problems resulting from human activities, and gives information that will help us evaluate the success of management programs.